Vuill. 1901

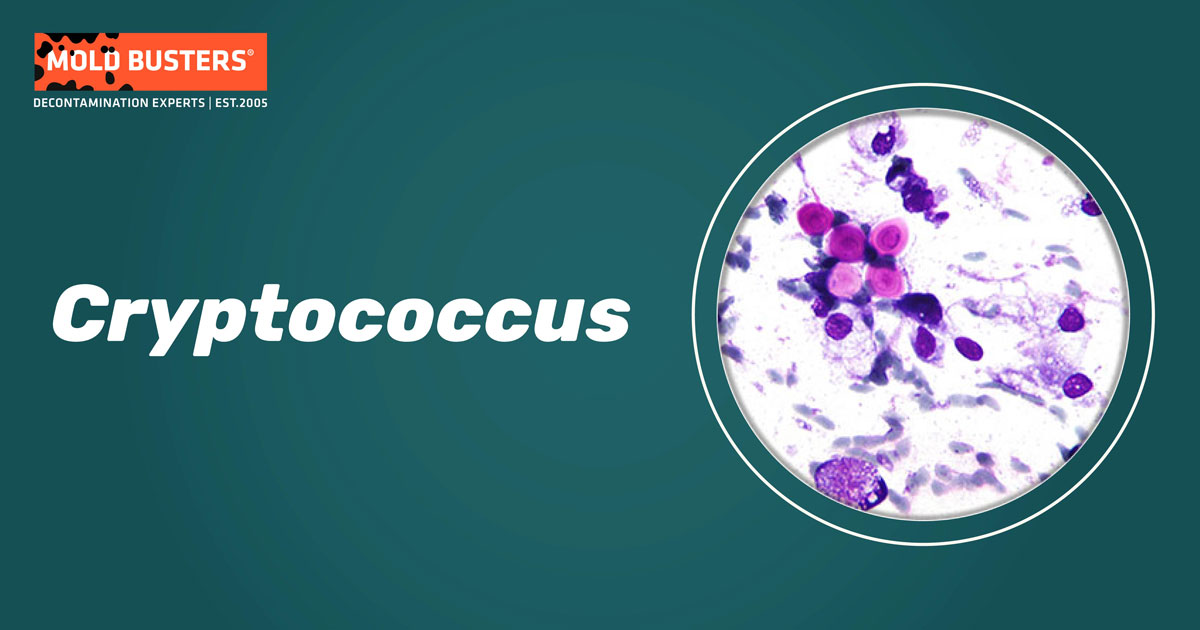

What is Cryptococcus?

Cryptococcus is a ubiquitous genus of yeast-like fungi. They grow as single-celled organisms, some having the ability to encapsulate themselves. Several species cause cryptococcosis, a potentially fatal disease, especially in individuals with weak immune systems. The sexual (teleomorph) forms of Cryptococcus are filamentous fungi in the Filobasidiella genus.

Although cryptococcosis was identified in 1894, it only became recognized as a major threat to human health with the onset of the AIDS pandemic in the 1980s. While mostly known as a disease of the immunocompromised, minor outbreaks of cryptococcosis in otherwise healthy individuals in North America and Canada (known as the Pacific Northwest outbreak) have caused the genus to gain even more attention [1].

Cryptococcus species

There are about 37 species of Cryptococcus that have been identified by scientists. However, as this genus is of extreme interest, its taxonomy is constantly being re-evaluated. Although virulent, Cryptococcus spp. is not infections and cannot be transferred from one organism to an organism. Most species colonize the soil and are not harmful to humans. Nevertheless, pathogenic species are widespread and present a danger to many people worldwide. Here is a list of a few of them:

- Cryptococcus neoformans –medically most relevant Cryptococcus species. It is a major human pathogen best known for causing severe forms of meningitis and meningoencephalitis.

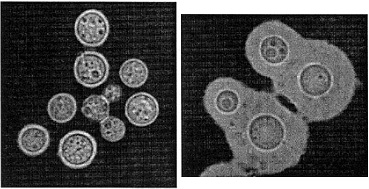

Figure 1. C. neoformans encapsulated cells (Photo source: CDC/Dr. Leanor Haley, Wikimedia)

- Cryptococcus gattii – Formerly a variant of C. neoformans, it has recently been separated into a distinct species. C. gattii is capable of causing disease sometimes even in non-immunocompromised people. It is predominantly found in tropical climates, but cases have been described in the Pacific Northwest [2, 3].

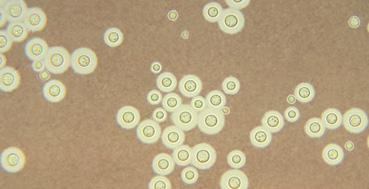

Figure 2. C. gattii (Photo source: CDC, Wikimedia).

- Cryptococcus albidus – Although not a frequent human pathogen, C. albidus causes pulmonary cryptococcosis and meningitis in those whose immune systems are incompetent such as people with lymphoma, HIV/AIDS, and leukemia.

- Cryptococcus laurentii – Just like C. albidus, it also leads to moderate to severe disease in immunocompromised individuals such as HIV/AIDS and cancer patients.

Non-infectious Cryptococcus species include C. aquaticus, C. bhutanensis, C. adeliensis, C. phenolicus, C. consortionis, C. vishniacci, C. ater and many others.

Where does Cryptococcus usually appear in home?

- C. neoformans is particularly abundant in bird droppings, like those of pigeons. It can also be found in various decaying organic materials, especially within the hollows of trees. It can be therefore present in soil and dust mixed with bird droppings.

- Aside from bird droppings, Cryptococcus can be found in the soil, in dust, and on trees. There are likely many more environmental reservoirs of Cryptococcus that have not yet been defined.

- Pigeons have been recognized as a major vector of Cryptococcus in urban and suburban settings [1]. If there is a specific place in your home that is frequented by pigeons, be on the lookout for pigeon droppings. It could be your garden, roof, balcony, attic, or anywhere else.

- This kind of mold could also exist on rooftops where pigeons land and leave their droppings. If there is a specific place in your home where pigeons like, be on the lookout for pigeon droppings. It could be your basement, garden, roof, balcony, or anywhere else.

- Pets and other domestic animals can also contract Cryptococcus. If you have pets or keep domestic animals keep a lookout for signs of Cryptococcus.

Health Effects of Cryptococcus

Cryptococcus is very dangerous as it causes cryptococcosis, a potentially fatal disease. Depending on the site of infection, cryptococcosis can be divided into three categories:

- Wound or cutaneous cryptococcosis

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis

- Cryptococcal meningitis

Globally, this disease affects approximately 1 million people per annum, with over 600 000 of them having a fatal outcome. As evidenced by the numbers above, cryptococcosis is often fatal, even when treated. Estimated fatality rates differ by region, from 9% in high-income regions, 55% in low/middle-income regions, and up to 70% in sub-Saharan Africa [5], where it has surpassed tuberculosis as the most lethal opportunistic infection of AIDS patients [6].

Symptoms of Cryptococcosis

Cryptococcus spp. causes cryptococcosis, most often starting in the lungs. This is a very dangerous condition, even with fatal outcomes if left untreated for long. In cases where a lung infection develops, it has signs that can be confused for pneumonia, such as coughing and shortness of breath. Sharp chest pain and bloody sputum also result from its effects on the lungs.

However, although cryptococcosis is contracted by inhalation, the most common clinical manifestation is meningitis. Symptoms typically develop within 1-2 weeks and include fever, malaise, headache, stiffness of the neck, photophobia, nausea, and vomiting [7].

Diagnosis and treatment of Cryptococcosis

Cryptococcosis is medically diagnosed by taking samples of cerebrospinal fluid and examining them through culture and immunodiagnostic tests. The culture of infected fluid will develop cream-colored colonies within 3-7 days. After diagnosis, cryptococcosis is treated by the use of antifungal medication, such as amphotericin B, flucytosine, and fluconazole. Unfortunately, in many cases the treatment is ineffective.

How is Cryptococcosis contracted?

Cryptococcus is an airborne fungus. Inhaling dust that contains Cryptococcus introduces the spores into your lungs. It first attacks the lungs before disseminating through the blood to other organs, notably the brain.

However, avoiding Cryptococcus isn’t something you should worry about too much, as chances are you’ve already come into contact with it. If you’ve ever been to a park, you’ve likely been exposed to Cryptococcus. A lot of children above the age of 2 are already been exposed to and are producing antibodies against C. neoformans [8]. However, just because we have antibodies against it doesn’t mean it’s safe to inhale large amounts of this fungus, especially in prolonged exposure.

Cryptococcus has a remarkable capacity to avoid and deceive the immune system (even using phagocytes to spread within the body) and can result in latent infections with no symptoms. This latent infection can subsequently surface, perhaps even years after contraction, causing serious illness [1]. These fungi are capable of surviving cellular phagocytosis (ingestion and digestion by the cells of the immune system), and can thus utilize host phagocytes to spread within the body.

How to get rid of Cryptococcus?

As with most fungi, adequate sanitary conditions are the best way to avoid any infections. To get rid of Cryptococcus spp., bird droppings must be removed. In addition, ensure that your immediate environment does not support bird roosting. In most cases, putting up anti-roosting spikes, netting, and sealing of any points of entry will do the trick.

You can use professional services like those offered by Mold Busters to ensure your home is clear of Cryptococcus. We have a proven track record when it comes to dealing with fungi and we have the experience and the technology needed to make your home secure.

Did you know?

Chaetomium is the 2nd common toxic mold type found in homes we tested?! Find out more exciting mold stats and facts inside our mold statistics page.

References

- May RC, Stone NR, Wiesner DL, Bicanic T, Nielsen K (2015). Cryptococcus: from environmental saprophyte to global pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol. 14(2):106-17.

- Lindberg J, Hagen F, Laursen A, Stenderup J, Boekhout T (2007). Cryptococcus gattii risk for tourists visiting Vancouver Island, Canada. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 13 (1): 178–9.

- MacDougall L, Kidd SE, Galanis E, Mak S, Leslie MJ, Cieslak PR, Kronstad JW, Morshed MG, Bartlett KH (2007). Spread of Cryptococcus gattii in British Columbia, Canada, and detection in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 13 (1): 42–50

- Animalu C, Mazumder S, Cleveland KO, Gelfand MS (2015). Cryptococcus uniguttulatus Meningitis. Am J Med Sci. 350(5):421-2.

- Park BJ, Wannemuehler KA, Marston BJ, Govender N, Pappas PG, Chiller TM (2009). Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 23 (4): 525–30.

- McDonald T, Wiesner DL, Nielsen K (2012). Cryptococcus. Curr Biol. 22(14):R554-5.

- Mada PK, Alam MU (2019). Cryptococcus (Cryptococcosis). In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Goldman DL, Khine H, Abadi J, Lindenberg DJ, Pirofski La, Niang R, Casadevall A (2001). Serologic evidence for Cryptococcus neoformans infection in early childhood. Pediatrics. 107(5):E66.

Get Special Gift: Industry-Standard Mold Removal Guidelines

Download the industry-standard guidelines that Mold Busters use in their own mold removal services, including news, tips and special offers:

Written by:

John Ward

Account Executive

Mold Busters

Edited by:

Dusan Sadikovic

Mycologist – MSc, PhD

Mold Busters

Figure 1. C. neoformans encapsulated cells (Photo source: CDC/Dr. Leanor Haley,

Figure 1. C. neoformans encapsulated cells (Photo source: CDC/Dr. Leanor Haley,  Figure 2. C. gattii (Photo source: CDC,

Figure 2. C. gattii (Photo source: CDC,